On a recent visit to Azimganj in Murshidabad, a slow sail on the Bhagirathi. Evening descended calm and cool, all around, on either bank was once Baluchar. The river shifted and the story of Baluchari changed course.

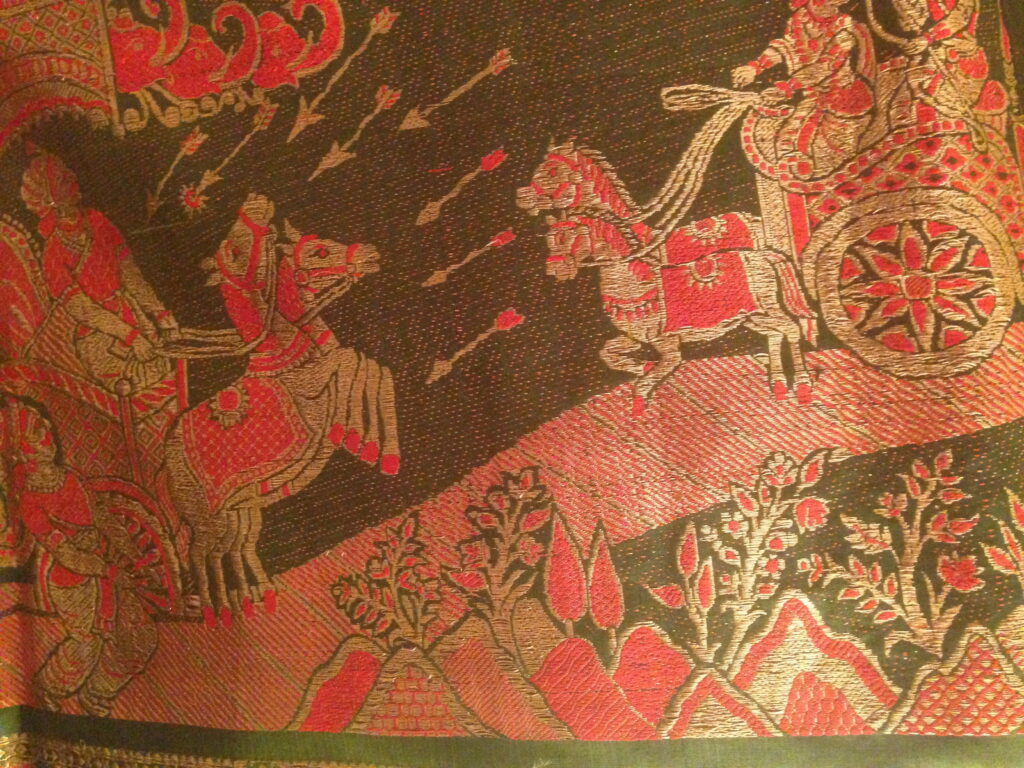

Golden arrows rained down, a charioteer looked back at the archer standing behind him. Who was he shooting at? I looked to the left. A man stood on another chariot holding the reins as a pair of horses reared, one of the chariot’s wheels seemed to be stuck in the mud and a warrior in reddish orange and gold was beside it, perhaps trying to get it out. Who were they?

Even though my mind wasn’t articulating clearly, I knew it was Karna… a terrible death approached on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. There were Arjun and Krishna on that chariot and the valiant, righteous, unspeakably wronged hero of Mahabharata was going to die right here on the añchal of my saree.

Karna, about to be struck, in a woven still frame draped on me.

I continued with my inspection of the motifs on a favourite Baluchari saree in green. Soon, at the edge of pallu/añchal, in neat squares, came up the visual of a newborn in a basket, little waves patterned below it, a woman knelt in front, and up there was the sun. Beside it was the sun god Surya, Karna’s father, blessing the baby. The birth and abandonment of Karna. His mother, the not yet married Kunti who merrily disposed of him, has just pushed him onto the Ganges. Did she ever wonder if her first born, whom she had without thinking of the consequences, might die? Did she even care? No one was fair to Karna i thought, his mother, Indra, Draupadi… no one, perhaps not even Krishna. Maybe that’s why the unassailable loyalty to Duryodhan, who was wrong but who gave him face, trust, even love.

In another motif, it looked like Karna being blessed by Parashuram; in a stylised paisley or kalka, stood Krishna with his peacock feather decked headband and Sudarshan Chakra. I couldn’t recognise the story on the border, of a man and a woman in a forest, she stroking a beautiful deer. The butas or motifs on the body of the saree were of a girl with a deer.

The weaver might have told two stories from the Mahabharata in this saree. I wasn’t sure. I’d first heard of Balucharis when I was around twenty, they were silks from Bishnupur in West Bengal, and they had complete tales from our mythologies woven in their borders and pallus. Sarees that were like story books. I had been fascinated, my mother though said she didn’t like sarees with not too well crafted human forms and animals all over them. No wonder I’d never seen a Baluchari in her wardrobe.

My very first Baluchari was my younger brother’s wedding gift to me. A smooth thick silk in cream, with elegant small paisleys on the body in subtle brown and a sleek vibrant blue, borders and pallu with fine weave in the same colours. I never looked carefully at the pictures, never “read” the story, just loved the feel of the whole thing. The saree is gone now, frayed and torn, but the memory stays.

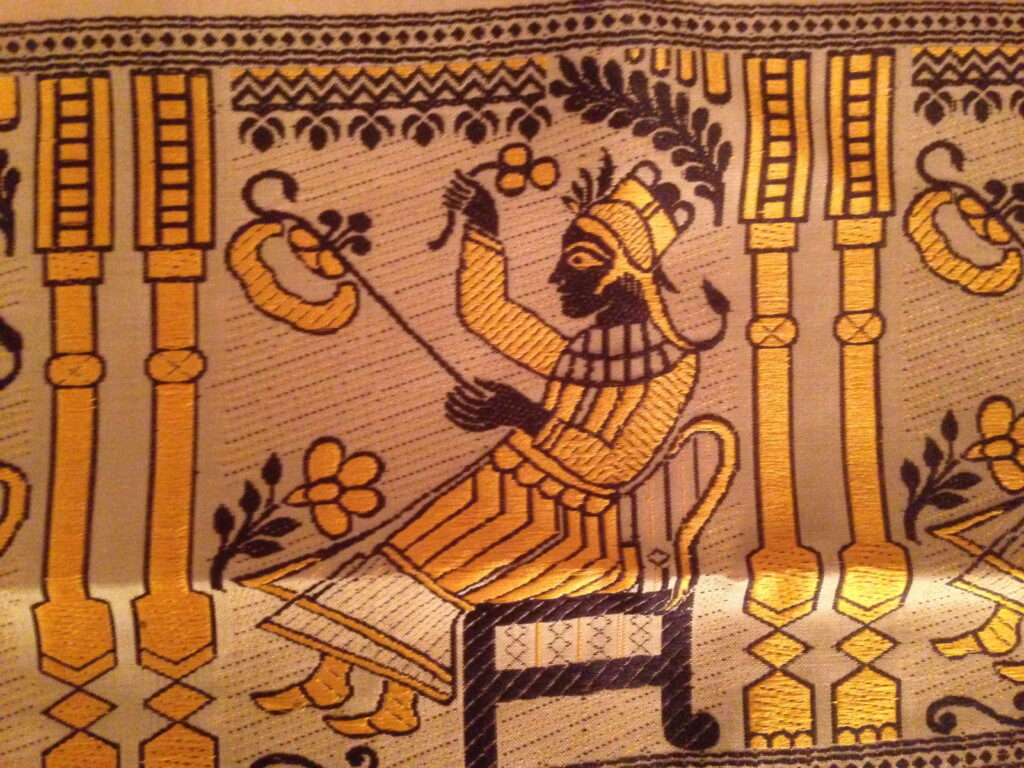

Soon after losing the saree, I heard that a dear aunt of mine had a Baluchari seller visiting her regularly, with sarees straight from the weavers. The green one here and that other grey and black one with highlights of yellow and motifs that look clearly like something from the Mughal era, perhaps the Sultans of Bengal, both are from her Baluchari man. She has bought me several over the years. Bishnupuri silk is dense yet light with a smooth svelte feel. The sarees are so easy to wear. And I can’t get over the colour combinations, from elegant to completely unorthodox; sometimes you’ll see the brightest/strangest shades on a saree and yet the effect will be classy and poised. My aunt always remarks on the innate ability of the “tñaati,” the weaver… and the very small amount of money we pay for these absolutely non-designer unusual pieces. I think the most I’ve paid for a baluchari has been rupees ten thousand.

While pondering on the Baluchari, my thoughts suddenly went to another famous battle field. Polashir juddha, the battle of Plassey. I thought of Robert Clive, all of thirty two or whatever he was at the time when he won the battle and established a British company’s rule on a part of India. Why was i thinking of Clive, I wondered. What was the saree trying to tell me?

Baluchar, which means sand bank, was a small town on the banks of the river Bhagirathi, a tributary of the Ganga. In the early 1700s, Nawab Murshid Quli Khan – the Diwan of Bengal under Aurangzeb, and later the first Nawab of Bengal – moved his Diwani office from Dhaka/Dacca to Maksudabad to the west. Born Surya Narayan Mishra somewheere in the Deccan, he had been sold to a Persian Muslim gent as a child, and was converted and raised as Mohammad Hadi. A sharp, capable young man, he was noticed by Aurangzeb, and in time became the Diwan of Bengal. After receiving the title of Murshid Quli from Aurangzeb, he renamed the city Murshidabad (nice Nawabi thing to do, I guess). The Baluchari came into being around this time and became popular. The mulberry silk was locally cultivated, weavers from Gujarat may have been involved in the creation of its idiom and texture.

I was in Murshidabad recently, where I heard about the terracotta temples dedicated to Shiva, built by Rani Bhavani, the powerful zamindar of Natore, in the mid to late 1700s. Legends of a royal dream, of 108 temples built in a day, of a benevolent ruler who wanted to rival Varanasi’s prominence… they touched and lit the burnt earth figures and tales on the walls and pillars of the temples. The artists who had drawn and hewed the richly ornamented tiles, also the fine-crafted work itself, had influenced the Baluchari saree weavers some said.

The Bengal Subah, absorbed by the Mughals in 1576, was the empire’s richest province. At one point, apparently, its economy was worth 12% of the world’s gdp. After Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, although the Mughal Empire was in difficulties, Bengal continued to thrive. Murshidabad was a flourishing and cosmopolitan trading port with many Marwari traders, Oswal Jain bankers, Gujaratis, Armenians, Arabs, Jews, Dutch, French, English, and other merchants. Bengal was known for its textiles. Muslin had become legendary, silks of all kinds were traded here. Baluchari also found its foreign takers. Its motifs back then reflected the life of the Mughals, the court, the landowners, etc., and held up a picture of the times.

When Clive and company rule arrived in 1757, and the capital moved to Calcutta twenty five years later, the Baluchari continued to flourish. It neatly adapted to its new environment, the motifs started to depict scenes from the life of the British, the changing world. If earlier there were nobleman on horses and elephants, now they were also on steamers, even trains. there were bibis with their hookahs and Englishmen in Indian gear.

But somewhere along the way, for all sorts of reasons, Baluchar lost its relevance and the weave almost perished. Thankfully, looms went up in Bishnupur in another district of Bengal and the craft continued. Master weavers such as Dubraj Das kept the tradition alive, adding new motifs and dimension. Interestingly, despite its intricate craftsmanship and rich stories, the sarees were not favourites among the wealthy ladies, Muslim or Hindu, of mid nineteenth century Bengal. Even the Brahmo Bhadramahilas preferred Banarasis, and rarely chose Balucharis… like my mother, I thought as I read that on a website. Perhaps the motifs were too edgy and not done to wear. Imagine a bibi smoking her hubble bubble, snuggling up to an Englishman in Angarkha and turban on your pallu. Okay, pass the smelling salts.

Balucharis might have disappeared but for the artist Shubho Thakur, who in the mid 1950s started reviving the art, and it’s most likely thanks to him, I have my sarees. I wonder when the motifs became those of our mythologies and left the realm of mere mortals and their shenanigans. I wonder also if there was ever one with the story of the battle of Plassey, of Clive, of the betrayal by Mir Jafar, Ghaseti Begum, Jagat Seth, Omichand, of Siraj ud Daula. Of how this language in which I write came and took root in our world.

Karna died, killed by his own brother. I just checked a pink and brown saree and here “Sitaharan” – the abduction of Sita in the Ramayana – was in progress, Ravan and Sita in a flying chariot, Jatayu trying to save her. A sense of Jatra, the Bengali folk theatre, in these silks. Who is that Mughal reclining on the border of the pale grey saree? That lovely girl in a ghagra? The man sitting on a chair holding up a three-leafed something and a fan? What is their story? Must call my aunt right now and tell her to get me another Baluchari.

Sarees Tell Stories | A green shot silk Baluchari with orange and gold zaree motifs/pallu/border and a pale grey Baluchari with black and yellow work, both from a Baluchari seller who comes carrying sarees from weavers, bought around 2007 and 2014 in Calcutta

……………………………………………………