It was a couple of years ago I think, that a good friend of mine said, since I loved sarees so much we should go to Chettinad together.

Chettinad?

I was surprised. What did Chettinad have to do with sarees? Chettinad was about chicken with a distinct peppery taste, which no matter how many recipes I looked up on the net, I never seemed to get right. It was about food: spicy, aromatic, delicious. It was about the famous Chettiars who travelled all over South East Asia, trading, lending money, being merchant bankers, and brought back the tastes of those countries to their traditional food.

Growing up in the north and east, I’d of course heard of cottons from South India. Kanchi cotton, Mangalgiri, Coimbatore… but never Chettinad. My friend smiled at my ignorance, and insisted, I had to see these beautiful handloom cotton sarees. Women weaved them usually, and like many of our gorgeous weaving traditions, this too was struggling to survive. Though efforts were on to revive it.

She also spoke of the palatial homes of the Chettiars, with their magnificent art and architecture, grand Belgian glass, Italian marble, chandeliers, and fine wood work. One had to see those too. In fact, one had to live in one of them. Her friend’s family had converted their home to a hotel, as many were doing, so the plan was to go and stay there for a couple of days, eat real Chettinad food – the vegetarian fare is fabulous as well, in fact, the Chettiars were originally vegetarians, I just read – and visit the weavers, buy lots of rich ethnic sarees.

Even planning this gave me a high. Then as happens with plans cooked up over a nice lunch, it didn’t really materialise. Time passed. Chandeliers swayed; pepper, nutmeg, cloves, and blue ginger were balanced by experienced hands; yarns were soaked in redolent earthy colours; another saree got woven. And every time my friend and I met, we averred, we must not forget to go on that trip.

A couple of weeks ago, I got a Whatsapp message: nowadays have you noticed, how Whatsapp messages seem to have hegemony over news of all kinds? From revolutions to religion to good morning wishes to jokes, the Whatsapp message delivers all, and delivers them first. This time it was an ad for an exhibition… of Chettinad sarees.

A friend of mine, whom I met only once in a while, had sent it. Her friends had been to Chettinad, and were completely enamoured of the sarees; they were also moved by the plight of the weavers. So they had picked up a handful for sarees and were having a sale. They planned to help the weavers with the profits. Since she knew I was sort of fond of sarees – ah, reputation, one must think what one would like to be remembered for – she had messaged me.

I was delighted and showed up early for the exhibition with the friend who had told me about these sarees in the first place. There weren’t too many pieces, but each one was beautiful. Too few sarees, too many women… alas. I managed to grab a couple, even as i looked longingly at a few that had already found their takers.

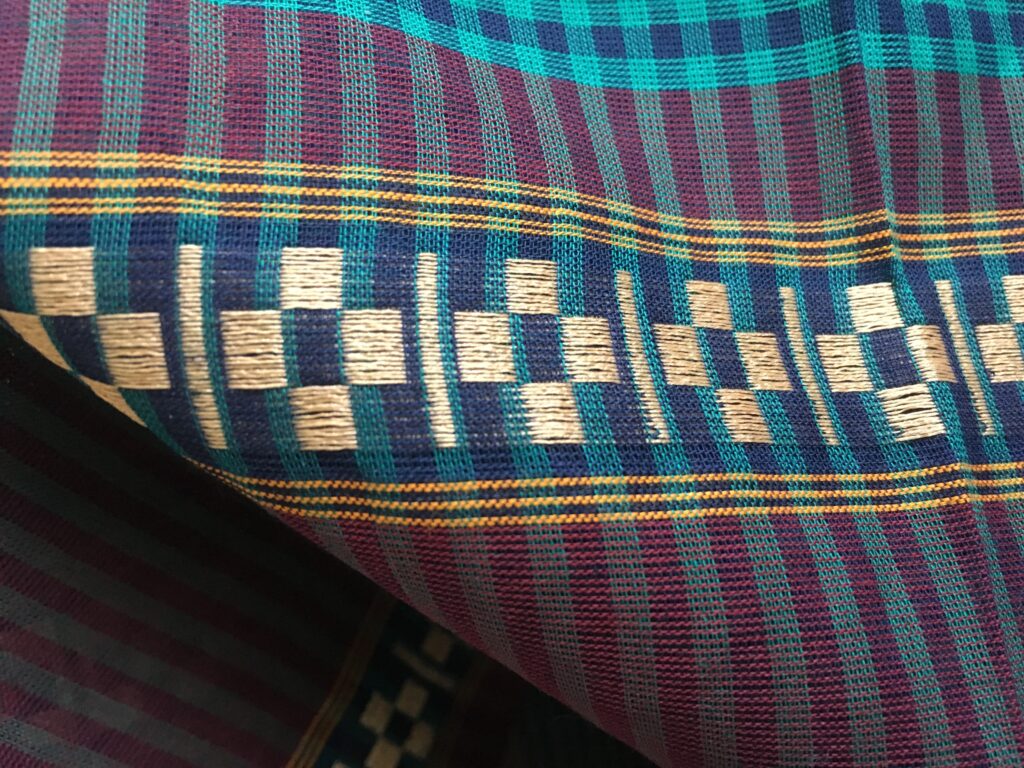

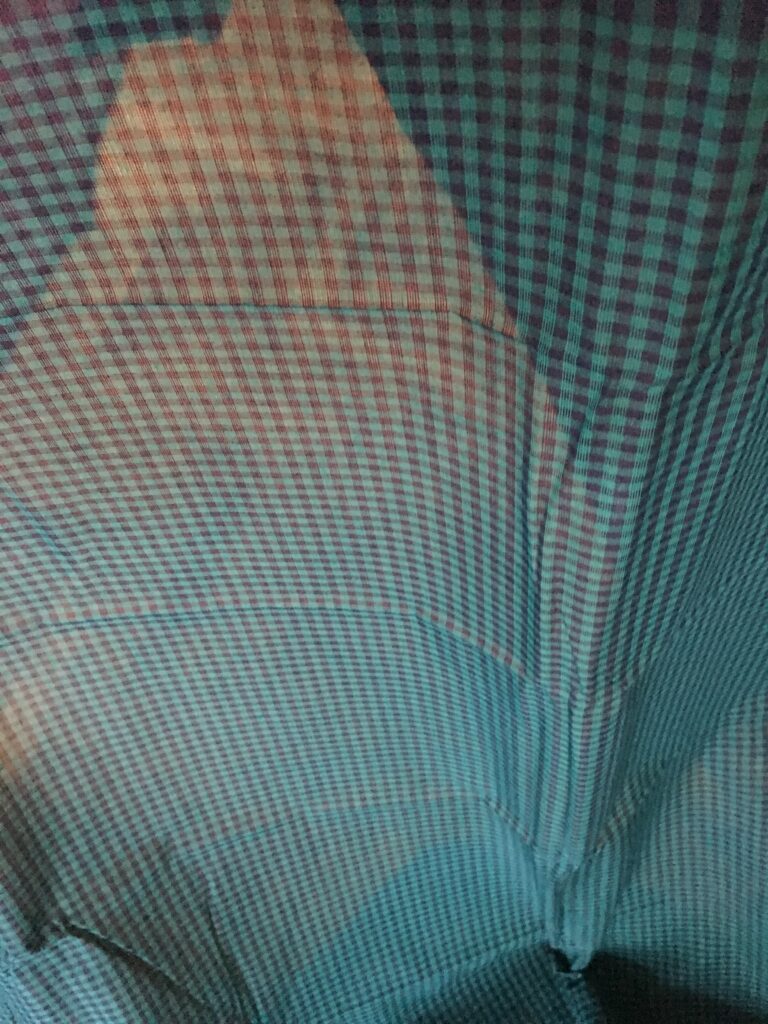

The cotton was slightly coarse in some, finer in others. The colours were unguarded, full, and luscious. A quality of gem stones in them. There was a boldness in the sarees’ demeanour: checks all over in contrasting tones or simple single colour body, edged by border in an off beat, at times flamboyant, shade. Well-articulated patterns and motifs. A touch of gold here and there. Or not. Just unusual tones and the elegance of unfettered cotton.

As I clutched my sarees and watched the video on the weavers and the mansions of Karaikudi, the main city of Chettinad, my mind wandered to streets and temples of Singapore, and a story with diverse threads searched for its connections, its warp and weft.

After coming to Singapore, I’d heard of the Chettiars, a community from India, who were once mainly money lenders. They’d come here early on, soon after the British took over in 1819. They operated from shops on Market Street, Chulia Street, and neighbouring lanes. Now of course, it’s all spiffy glass and concrete, and you don’t see the Kittangis, where they lived and worked. Living quarters upstairs, shops downstairs.

The Chettiar sat on the floor in traditional wear of white cotton, with his sacred ash markings on the forehead, and his mind alert and sharp; before him a low wooden desk with books and other necessities. The Chettiars were known for their financial acumen. The community, though, hadn’t always been money lenders, they were traders for centuries, dealing in salt, spices, and gem stones. Later as the British expanded their trade interests in the region, the wealthy merchants turned to money lending and finance.

The Chettiars came to Singapore long before the big banks had arrived in the region. Back then, they were perhaps the only people ready to offer a legitimate line of credit to small businesses, plantation owners, even larger enterprises. In a way, they were the first bankers and financiers around here.

The Kittangis, those unique shop houses, had only men, for the itinerant merchants initially didn’t bring their families over. The sons accompanied their fathers once they were around eight or nine years old. And from that age onward they were gradually trained in matters of business in a sternly disciplined environment.

While they lived away from their ancestral land, the Chettiars used their considerable wealth to build beautiful and ostentatious homes there. So they are are often referred to as Nattukottai Chettiars or “people with palatial houses in the countryside” or Nagarathars, city dwellers. Looks like, the homes were mainly inhabited by the women of the family, where they in all likelihood perfected and embellished their distinctive cuisine while draped in these gorgeous cotton sarees, just right for that arid, hot part of Tamil Nadu.

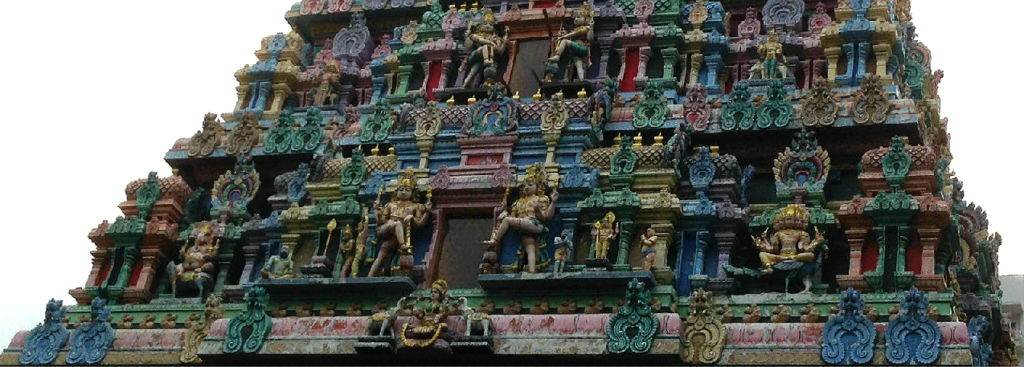

A few years ago, when I went to the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple on Keong Saik Street in the heart of Chinatown, I learnt that the temple was built by the Chettiars. One of the oldest Hindu temples here, on Tank Road, was built by them in 1859. The Chettiars were wealthy, they were hardworking, and they were highly religious. I had of course never connected sarees with these serious men in white.

On a walk in Singapore, just off River Valley Road, I’d come across three roads named after three men of the community. Obviously these were people of importance and they must have contributed something to this country to have been honoured so. Today, the Chettiars who live here are no longer money lenders, they are professionals in various fields, and highly regarded many of them.

The Chettinad sarees were getting slightly wrinkled in my hands as i thought about all these things, and women I barely knew smiled at each other and me as well, as we spoke of the Karaikudi palaces, the houseproud Aachis who cooked wonderful authentic dishes, the women who weaved, their needs, their artistry, their warmth, the weather, a different life far away, its only hint in the colours and fabric we all held close.

Some day, my friend and I must go on that trip, yes, we must.

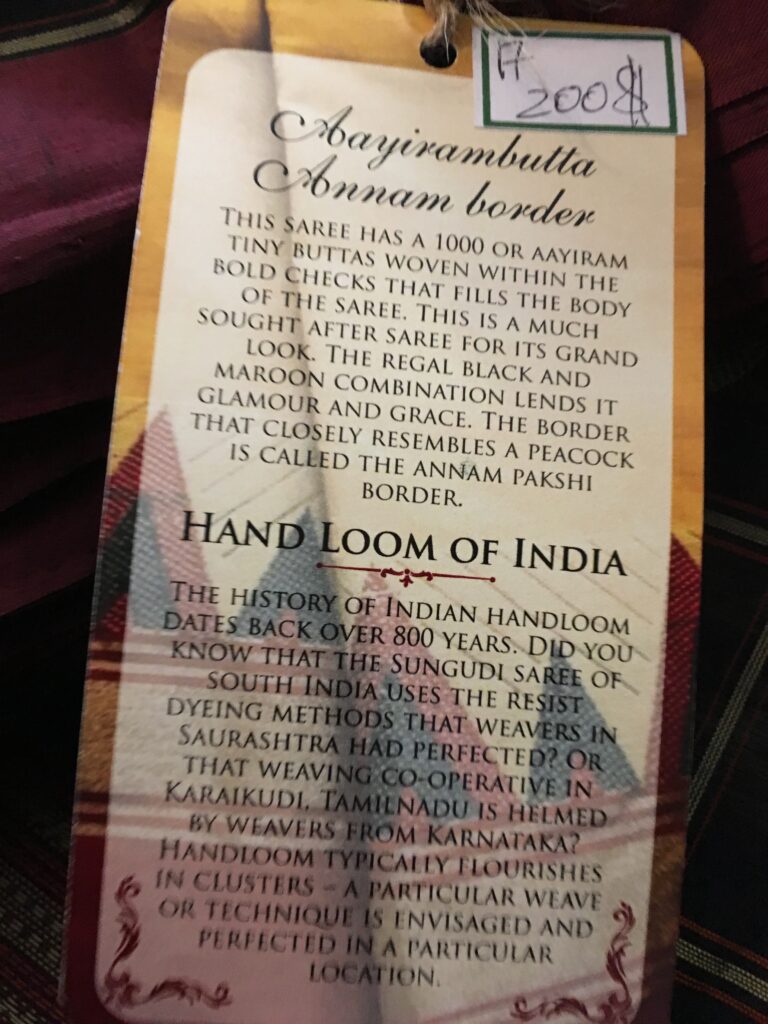

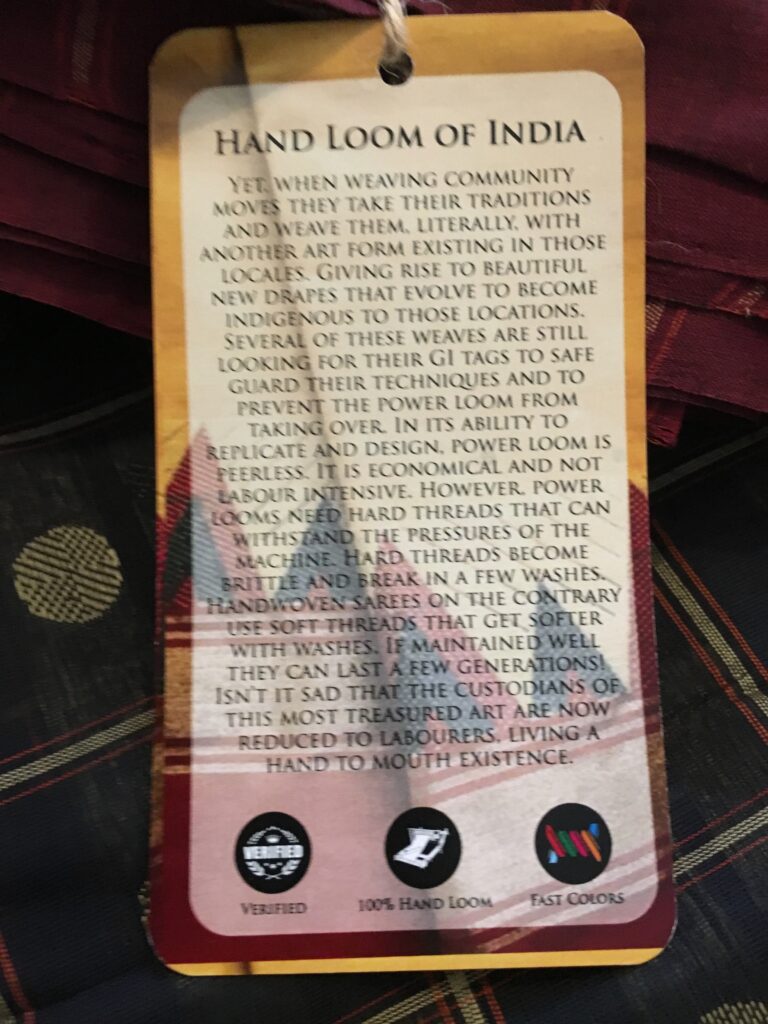

My saree with one thousand Aayiram or buttas/motifs within the checks.

The quintessential checks of Chettinad sarees.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Sarees Tell Stories | Turquoise and navy checks with a purplish maroon border; and beige with a thousand red buttas and checks in red and turmeric with a plain turmeric border… two Chettinad sarees from an exhibition in Singapore, November 2018.

The majestic Tank Road Temple built by the Chettiars.